Reactive endpoints: pushing data to the frontend

Despite being on the web where millions or billions of people move around every day, web applications always tend to start out as being single-user applications. Not in the sense that only one user can log in or one user can use the application at a time but, as a user of the application, you don’t really see that other people are also using the application. Maybe, once in a while, you’ll get an error message that somebody else changed some data and caused a conflict, but that’s it.

The technical explanation behind this is simple: all actions are browser/user driven and the server merely responds with new data that is used to update the UI. The server never proactively tells you that another user or a system is doing something that you should be aware of.

This is not how the real world works, though. Imagine trying to buy a coffee and not being able to see if there are other customers in the café. Only by trying to order from the person behind the counter would you get a response that "Somebody else is ordering a coffee right now, try again later".

Enter server push, so that you can allow the server to take an active role in your application.

Reactive endpoints: pushing data to the frontend

Communication in Hilla is built around methods in endpoint Java classes published to the browser. You call an endpoint and get a response. With server push, it is similar but not exactly the same. An endpoint method that can send many values to the client looks like this:

@Nonnull

public @Nonnull Flux<@Nonnull String> sayHello(@Nonnull String name) {

return Flux.just("Hello " + name, "Hallo " + name, "Hej " + name);

}Flux? What? Let's get back to that in a while. The browser-side code looks like this:

MyEndpoint.sayHello("John").onNext((value) => {

Notification.show(value);

});Endpoint methods that return a Flux in Java will provide a subscription on the browser side. The onNext callback in the subscription is called whenever the server sends a message, so with this code we will see three subsequent notifications saying "Hello John", "Hallo John" and "Hej John".

In this case, the just method of Flux will send the listed values directly one after the other, but if we add .delayElements(Duration.ofSeconds(1)) after the just call, we’ll get one notification popping up every second, instead.

While the above does not feel like the server taking an active part, it’s just the beginning.

A Flux is rarely ever used through the just method but, instead, is connected to something that emits events or other Fluxes.

Flux and Project Reactor

So what are these Fluxes, really? Flux is "an asynchronous sequence of 0-N items, optionally terminated by either a completion signal or an error", as defined by the Project Reactor docs. A Flux can emit values based on another Flux, it can transform values, and have 0-N subscribers that join and leave over time. It’s a bit like a Java stream but it’s always asynchronous and can emit zero values, a given number of values, or be infinite. It can have many listeners that join and leave as time passes. It’s a publisher you subscribe to when you’re interested in what it emits.

In the above example, we used a Flux that emitted three strings and then completed, with no or a 1-second delay between emitting the values. More realistic Fluxes would be, for example, a Flux that connects to a database using R2DBC and requests some data. Then, whenever the database emits some data, some part is picked out, transformed, and then passed on to an endpoint Flux, which in turn passes it on to the subscriber in the browser. With some databases, you can even listen to changes at the database level and reactively get those changes to the browser, as in this more advanced example.

To learn more about reactive streams, Fluxes, and reactive programming, see the project reactor reference guide.

Interactivity between users

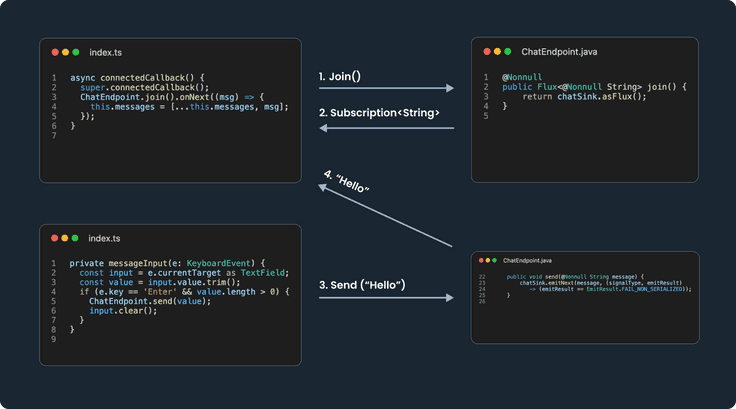

Now that we have some idea about what a Flux is, let's briefly investigate a chat implemented using a Flux and Hilla. To implement a simple chat, you need a way for one user to submit a message to all other users. This can be accomplished by creating a sink, which is a way to programmatically send data into a Flux:

Many<String> chatSink = Sinks.many().multicast().directBestEffort();Using chatSink, we can emit messages so that anybody who has subscribed to the corresponding Flux (chatSink.asFlux()) will get the messages.

The chat then consists of two endpoint methods.

One endpoint is for sending messages:

public void send(@Nonnull String message) {

chatSink.emitNext(message, (signalType, emitResult) -> (emitResult == EmitResult.FAIL_NON_SERIALIZED));

}The failure handler (second parameter) tells the Flux to try again if multiple people write messages at the exact same time.

The other endpoint method is for subscribing to the messages:

@Nonnull

public Flux<@Nonnull String> join() {

return chatSink.asFlux();

}That's it. In the browser, we subscribe to the messages:

ChatEndpoint.join().onNext((msg) => { … })and then handle them in an appropriate way.

A working chat is available at https://github.com/Artur-/hilla-chat/

What then?

Push is available starting from Hilla 1.1.0-alpha3. To try it out, create a new project using the pre-release:

npx @vaadin/cli init --hilla --pre --push my-projectPush support is still experimental and behind a feature flag until we finalize everything surrounding it. There might still be some changes here and there.

Happy Fluxing!